New Year, Same Great Films

4 January 2018

New Releases A Happy New Year from everyone at Filmhouse! We're looking forward to...

In his Cave Allegory (Republic, c.360 BCE), Plato presents a strikingly visual account of the distinction between knowledge and belief and, in doing so, provides us with what may be considered the earliest cinema.

Plato invites us to imagine humanity as prisoners who have been captive since birth in an underground chamber. There they sit, facing the back wall of the cave, unable even to turn their heads. Behind them, and higher up, a fire is burning, and between the fire and the prisoners runs a road, along which a wall has been built. Along the road there are men carrying artefacts, and the fire projects shadows of these artefacts onto the back wall of the cave. The prisoners, states Plato, would believe that the shadows of the objects were the whole truth.

In what follows, we are asked to consider what would happen were one of the prisoners to be compelled to stand and turn to face the fire, and then dragged out into the sunlight. Although this would be dazzling and they would be bewildered at first, eventually, says Plato, the released prisoner would come to realise that what they used to take for reality was nothing but shadow and illusion, and they were now seeing things more clearly.

The meaning of Plato’s allegory is manifold, it reveals his view of reality (metaphysics) and his related position on knowledge (epistemology). It can also be seen as representative of the nature of philosophy in general - as the attempt to subject received wisdom and preconceived beliefs to doubt, with the aim of replacing error for truth.

In addition, Plato’s Cave may strike us as very similar to the modern cinema. The cinema audience watches images projected onto a screen in front of them, these images are projected from a piece of film being moved past a light behind them, and the images on this piece of film are themselves merely copies of the real things outside the cinema.

This resemblance between the structure of the cave and the cinema entails a similar correspondence between Plato’s prisoners and cinemagoers. Of course, there are also important differences. Modern film audiences know about the outside world and its relationship to the film they are watching, whereas Plato’s prisoners only know the shadow world. Therefore, although the modern cinemagoer can be drawn in by fictions, they remain aware of the fact they are fictions. As such, film can fulfil an important philosophical role by providing us with an array of images and scenarios that can cause us - in much the way Plato’s allegory - to question ourselves and the world around us.

As well as being representative of the cinema in general, Plato’s allegory of the cave can be found in many films, most notably, Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Conformist (1970). This video-essay combines scenes from The Conformist, along with an Orson Welles reading of Plato’s text in order to show how the imagery of the Cave permeates throughout.

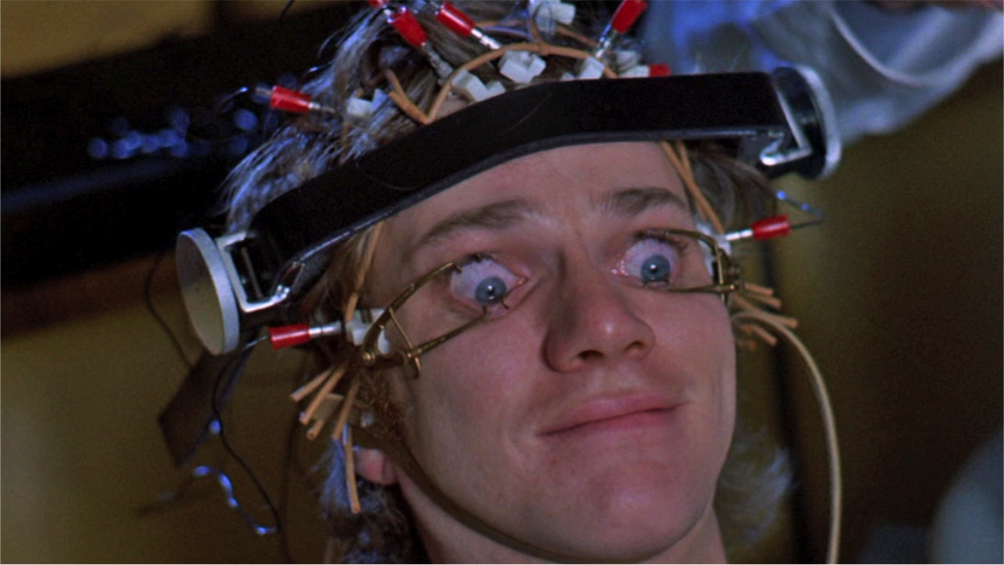

The three films in the current Filmosophy season also resound with the images and ideas of Plato’s Cave, allowing insight into the value of friendship and love (Cinema Paradiso), the power of film to both liberate and control (A Clockwork Orange), and the questionable reality of our world (The Truman Show).

James Mooney

Lecturer in Film and Philosophy

The University of Edinburgh

www.facebook.com/thinkingfilm

www.twitter.com/film_philosophy

www.instagram.com/filmphilosophy

Have a look at what's on to book a screening or event.

Still adding?

If you don’t want to view your Watch list right now, you can access your list anytime from your profile.